The Holly Golightly Sweepstakes

Before Truman Capote's Swan scandal, who inspired "Breakfast at Tiffany's"?

Hello friends! I’m not gonna lie: Today’s newsletter is pretty epic. I may have gone a wee bit overboard writing about a classic book and film. In the immortal words of Frank Navasky, “thank your” for reading You’ve Got Mail. I hope you enjoy it.

Doris Lilly could not contain her glee.

It was the fall of 1958 and she had just read her friend Truman Capote’s new novella, Breakfast at Tiffany’s. The socialite and writer instantly recognized herself in his fabulously eccentric heroine, Holiday “Holly” Golightly. She phoned their mutual pal, Andrew Lyndon, who sensed that Lilly was fishing for confirmation.

“Have you read Truman’s new book?” she asked, according to Capote biographer Gerald Clarke.

“Why, yes,” Lyndon said. “Truman sent me a copy, and I enjoyed it very much.”

“It’s me! It’s me! It’s me!” Lilly blurted out.

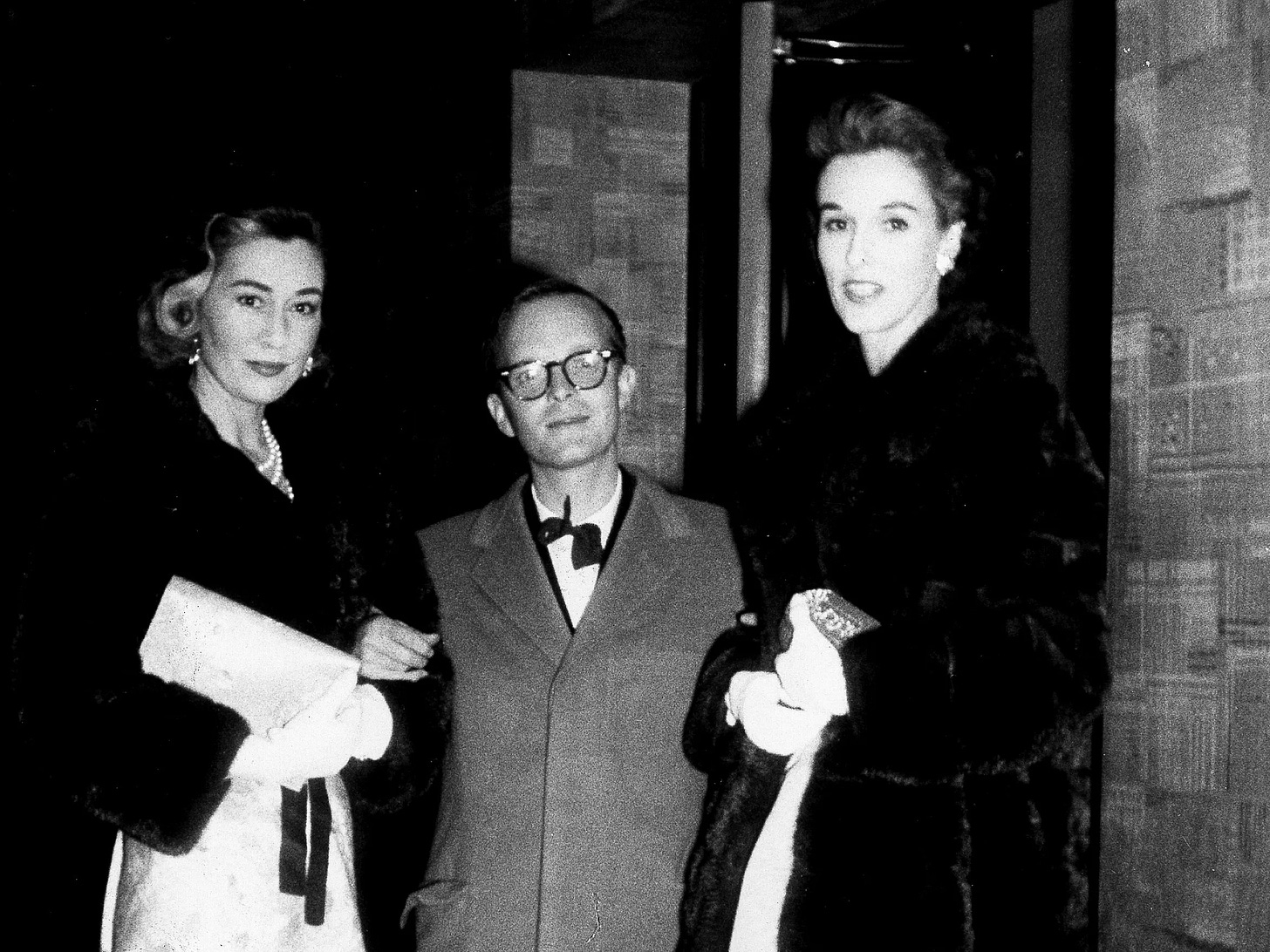

Later, Lyndon told Capote about Lilly’s reaction to Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Capote replied: “Honey, you tell her, her, her for me, me, me that it is her. But it’s also Carol Marcus and Oona Chaplin.”

As Clarke wrote in his definitive biography of the celebrated author, “With publication came what Truman called the Holly Golightly Sweepstakes: half the women he knew, and a few he did not, claimed to be the model for [Holly].”

Capote always said that Holly was his favorite character to write. He enshrined her in Breakfast at Tiffany’s 17 years before Esquire published “La Côte Basque, 1965,” the thinly veiled short story that sparked an uproar among New York high society and targeted his “swans,” the socialites who had trusted him with their deepest secrets. It is Capote at his most brutal and biting and self-sabotaging. It made him a Park Avenue pariah and hastened his downward spiral into substance abuse and personal ruin. It is the subject of the new FX series Feud: Capote vs. The Swans, which explores the aftermath of the hit piece and unites a cast of ’90s icons to form the messy milieu at the center of the scandal. Tom Hollander — not to be confused with Tom Holland — does a fine job impersonating the titular enfant terrible, but Feud, with its muted Mad Men palette and overarching somber tone, rarely, if ever, captures the fizzy, fly-on-the-wall fun of reading the stories that Capote staged in his adopted hometown. His late-stage decline, as filtered through the horror-show lens of writer-producer Ryan Murphy, is tough to watch. (I don’t want to hang with Truman when they show him like this!!!)

In better days, he was a literary wunderkind. In Breakfast at Tiffany’s, his nameless gay narrator befriends Holly Golightly, a 1940s good-time girl who lives in the apartment next door. He observes:

I went out into the hall and leaned over the banister, just enough to see without being seen. She was still on the stairs, now she reached the landing, and the ragbag colors of her boy’s hair, tawny streaks, strands of albino-blond and yellow, caught the hall light. It was a warm evening, nearly summer, and she wore a slim cool black dress, black sandals, a pearl choker. For all her chic thinness, she had an almost breakfast-cereal air of health, a soap and lemon cleanness, a rough pink darkening in the cheeks. Her mouth was large, her nose upturned. A pair of dark glasses blotted out her eyes. It was a face beyond childhood, yet this side of belonging to a woman. I thought her anywhere between sixteen and thirty; as it turned out, she was shy two months of her nineteenth birthday.

Unlike the respectable, well-mannered heiresses whom Capote charmed, Holly (real name: Lulamae Barnes) is an imposter with humble origins. She’s a Texas child bride who married a veterinarian, then ditched him and fled to Manhattan. She’s worldly and libertine and blunt and magnetic, craving adventure above all. She should probably slow down and have a sandwich. “Holly Golightly was not precisely a call girl,” Capote told Playboy in 1968. “She had no job but accompanied expense-account men to the best restaurants and night clubs, with the understanding that her escort was obligated to give her some sort of gift, perhaps jewelry or a check ... if she felt like it, she might take her escort home for the night.”

While gilded domesticity had caged Babe Paley and other Midcentury swans, Holly mimics their tasteful aesthetic — but rejects the expectation to become a stay-at-home wife, an honest woman, and give up her blithe existence. Clarke wrote: “[Holly’s] whole life is an expression of freedom and an acceptance of human irregularities, her own as well as everybody else’s. The only sin she recognizes is hypocrisy. In an early version, Truman gave her the curiously inappropriate name of Connie Gustafson; he later thought better and christened her with one, Holiday Golightly, that precisely symbolizes her personality: she is a woman who makes a holiday of life, through which she walks lightly.”

Holly certainly captures the essence of the most vivacious ladies who lunched with Capote on the Upper East Side, yet she also represents another kind of woman whom he encountered. A woman who made her mark on the big city before saying goodbye to all that.

“Every year, New York is flooded with these girls; and two or three, usually models, always become prominent and get their names in the gossip columns and are seen in all the prominent places with all the Beautiful People,” Capote said in Playboy as the ’60s wound down. “And then they fade away and marry some accountant or dentist, and a new crop of girls arrives from Michigan or South Carolina and the process starts all over again. The main reason I wrote about Holly, outside of the fact that I liked her so much, was that she was such a symbol of all these girls who come to New York and spin in the sun for a moment like May flies and then disappear. I wanted to rescue one girl from that anonymity and preserve her for posterity.”

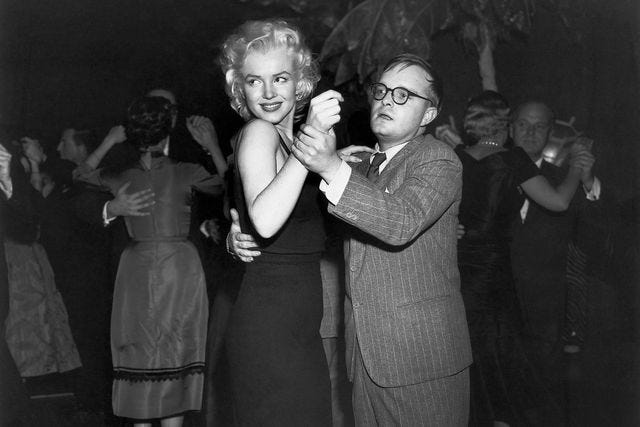

Capote sold his novella to Hollywood, which cast the enchanting Audrey Hepburn as Holly and gave the character a wider audience. In Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M., my favorite book of all time, Breakfast at Tiffany’s historian Sam Wasson reported that Capote had wanted Marilyn Monroe, not Hepburn, for the role. (He also, for a hot minute, wanted to play the male lead! But Paramount Pictures cast George Peppard instead and turned the “narrator” into a conventionally handsome straight guy and love interest for Holly, thus erasing Capote’s original dynamic: The powerful bond between a straight woman and a gay man. CC’ing his Feud coterie: Babe Paley, Slim Keith, C.Z. Guest and Lee Radziwill.)

Monroe, Capote felt, contained a poignant simplicity underneath her sexy surface. Once, channeling Holly, she confided to him, “I’ve never had a home. Not a real one with all my own furniture.”

But film producers Marty Jurow and Richard Shepherd controlled the picture and the casting, and they thought Monroe lacked Holly’s toughness. Hepburn, though. She was in her early thirties and not exactly known for her sex appeal. Attuned to the socially conservative 1950s, Jurow and Shepherd thought that wholesome Hepburn — who had a face beyond childhood, yet this side of belonging to a woman — could mitigate the risk of making a movie based on a book about a teenage lady of the night. And possibly win over, or fool, some pearl-clutchers.

Hepburn mastered the assignment. After Breakfast at Tiffany’s premiered in 1961, suddenly it seemed that everyone wanted to be Holly — and raid her closet filled with LBDs. She totally glamorized the urbane bachelorette lifestyle. (The following year, Helen Gurley Brown published the bestselling pre-feminist advice book Sex and the Single Girl, which endorsed premarital sex and offered tips on saving money and decorating an apartment kitchen to make it “sexy.”)

“It was the most miscast film I’ve ever seen,” a boozy Capote complained toward the end of his life, according to Wasson. “It made me want to throw up. Like Mickey Rooney playing this Japanese photographer” — god, that was awful! — “[and] although I’m very fond of Audrey Hepburn, she’s an extremely good friend of mine, I was shocked and terribly annoyed when she was cast in that part. It was high treachery on the part of the producers.”

In his perspective, “The book was really rather bitter and Holly Golightly was real — a tough character, not an Audrey Hepburn type at all. The film became a mawkish valentine to New York City and Holly and, as a result, was thin and pretty, whereas it should have been rich and ugly. It bore as much resemblance to my work as the Rockettes do to [ballerina Galina] Ulanova.”

Capote was a journalist to the core. His gossipy fiction stole from his rarified life as a raconteur, and well, Holly comprised a mixture of characters — including her creator. Behold some of Miss Golightly’s biggest inspirations.

Doris Lilly

Born and raised in California, Lilly moved to New York in search of a rich husband. She was tall and long-legged, recalled Gerald Clarke, and had “streaked blond hair” just like Holly. She had tried acting in movies, but only secured a single line in the Gary Cooper drama The Story of Dr. Wassell. She and Capote bonded in their freewheeling twenties. As Clarke observed, “she was bouncy and buoyant, not subject to moods or given to silences of more than thirty seconds.” She lived in a walkup apartment on East 78th Street; at one point, her landlord shut off her heat and electricity as punishment for failing to pay the rent. “Who thought about those things?” she remarked later. “I was so busy going out every night. I mentioned the problem to some man I was seeing, but instead of sending a check, he sent two dozen candles. Finally, it was so cold that Truman and I took the shelves out of the kitchen closet and burned them in the fireplace.” Capote encouraged Lilly to write her first book, How to Meet a Millionaire, which led to her career as a gossip columnist for the New York Post.

Carol Matthau

By the time Capote met Carol Marcus in 1942, she had already forged a reputation as a “licensed screwball,” which was how a mutual friend described her to him. She graced the society pages and partied at El Morocco and the Stork Club alongside fellow It Girls Gloria Vanderbilt, the heiress to a Gilded Age railroad fortune, and Oona O’Neill, whose future marriage to Charlie Chaplin, 36 years her senior, stirred as much controversy as “La Côte Basque.” The glamorous trio welcomed Capote into their circle, and he loved tagging along for the zany adventures. Marcus, a sometime actress, provided the novelist with endless comic material — merely through being herself. She was outspoken and rags-to-riches, having escaped poverty as a young girl when her mother married a wealthy businessman. “I think Truman wanted to climb inside my head, to understand how girls thought, their dreams and their reactions to whatever life threw at them,” she told journalist Noreen Taylor in 2001. Oozing snobbery, Capote sneered at her plans to wed actor Walter Matthau, her rumpled co-star in the Broadway play Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? “Darling, you have so many rich beaux,” he advised his hopelessly smitten muse, “why are you doing this? Go to bed with Walter and marry someone rich.”

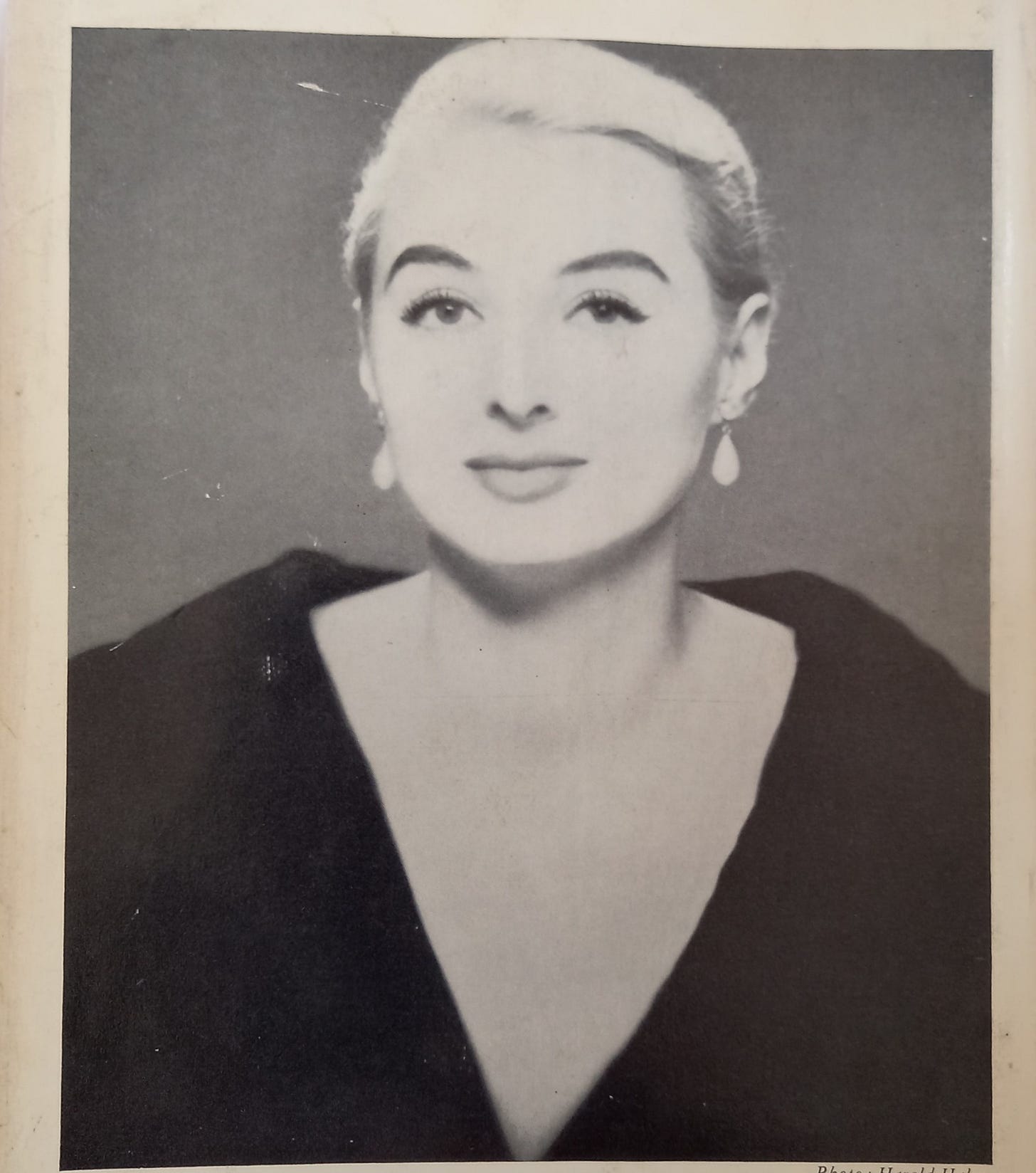

Joan McCracken

While Capote spent 1943 living it up, McCracken was originating the role of Sylvie in Oklahoma! at the St. James Theatre. She was a multi-talented dancer and actress with a comic timing that made her one of the hottest young stars on the stage. Her other credits included Broadway’s Bloomer Girl, a musical about a plucky young woman who prefers bloomers over skirts, and MGM’s Good News, a musical about lusty college students. McCracken was wild and provocative. According to her biographer, Lisa Jo Sagolla, she would do things like take off her shirt and bra during a work meeting with an MGM vocal coach. Why? To get “more comfortable.” From 1939 through the end of World War II, she was married to Jack Dunphy, a dancer who, like her, grew up in Philadelphia. Dunphy became Capote’s long-term partner in 1948; McCracken moved on to choreographer Bob Fosse — and personally made him happen — as Capote folded parts of her into Holly Golightly. McCracken once told Capote that she tore up her dressing room after receiving a telegram with the terrible news that her brother had died fighting in the war. Likewise, Holly spirals upon learning that her sibling has met the same fate.

A Mystery Woman Whom No One Remembers

Wasson’s Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M. quoted Capote as telling Playboy:

“The real Holly Golightly was a girl exactly like the girl in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, with the single exception that in the book she comes from Texas, whereas the real Holly was a German refugee who arrived in New York at the beginning of the War, when she was seventeen years old. Very few people were aware of this, however, because she spoke English without any trace of an accent. She had an apartment in the brownstone where I lived, and we became great friends. Everything I wrote about her is literally true — not about her friendship with a gangster called Sally Tomato and all that, but everything about her personality and her approach to life, even the most apparently preposterous parts of the book. For instance, do you remember, in the beginning, where a man comes into a bar with photographs of an African wood carving of a girl’s head he had found in the jungle and the girl could only be Holly? Well, my real-life Holly did disappear into Portuguese Africa and was never heard from again.”

Hmmmmmm. Capote told Clarke a version of this story in which the “Holly” was “Swiss,” not German. “Did she exist? Probably,” said his biographer. “But was she Holly Golightly? I doubt it. If she did exist, I suspect she was just one of the many.”

Nina Capote

Capote’s mother (real name: Lillie Mae Faulk) gave birth to baby Truman at a New Orleans hospital in 1924. She divorced his father four years later and abandoned her precocious son with relatives in Monroeville, Alabama. Aching to escape the South, the social climber sought to take a bite out of the Big Apple — and break into the haut monde. She called herself Nina. From time to time, “she would turn up unannounced, tickle Truman’s chin, offer up an assortment of apologies, and disappear,” Wasson wrote. At 8 years old, the boy joined Lillie Mae/Nina up North but her early absences did lasting damage to his psyche. Wasson again: “In consequence, [Truman] was equal parts yearning and vengeance, clutching at his intimates with fingers of knives that he would turn back on himself when left alone.” His mother, her Brooke Astor dreams dashed, died by suicide in 1954. With Holly Golightly, Capote got the chance to rewrite the tragedy and give it a rosier ending. Holly, the starry-eyed drifter off to see the world (cue “Moon River”), would live forever, adored beyond her wildest dreams.

Truman

But Holly, most of all, is a projection of Capote himself. She embodies his anxiety, which she dubs “the mean reds,” explaining, “You’re afraid and you sweat like hell, but you don’t know what you’re afraid of.” How does she cure them? She hails a cab to Tiffany’s on 5th Avenue. “It calms me down right away, the quietness and the proud look of it,” Holly says of the store. “Nothing very bad could happen to you there, not with those kind of men in their nice suits, and that lovely smell of silver and alligator wallets. If I could find a real-life place that made me feel like Tiffany’s, then I’d buy some furniture and give the cat a name.”

Truman, wherever you are, I hope you’ve found some peace.

You made it. Bless. I vow to keep it short going forward! But while I still have you here, I’d like to recommend two newsletters I loved this week: Becca Freeman’s “In my Nora Ephron Era” is a sheer delight and W. Kamau Bell’s heartfelt tribute to Tracy Chapman hits all the right notes. (Be right back, I’ll be watching Chapman and Luke Combs perform “Fast Car” at the Grammys for the 200th time since Sunday.)

Yours in bouquets of newly sharpened pencils~

Erin

This turned out terrific.

Amazing. I learned so much and really enjoy your writing. Thank you